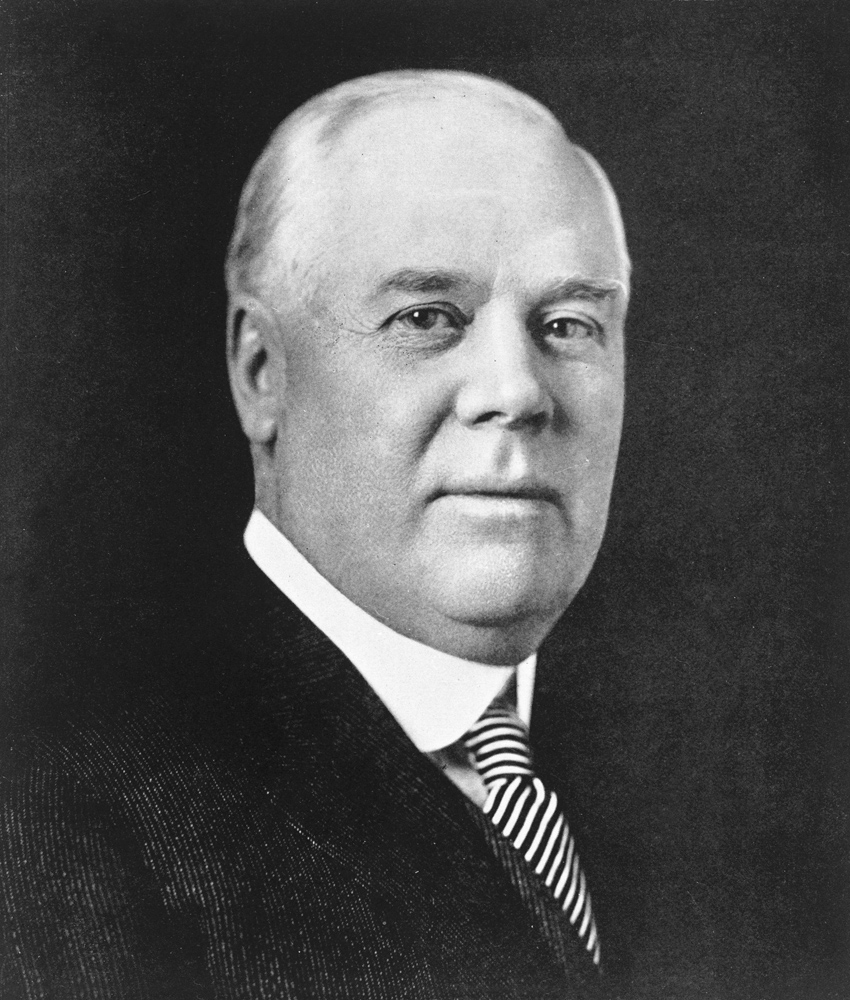

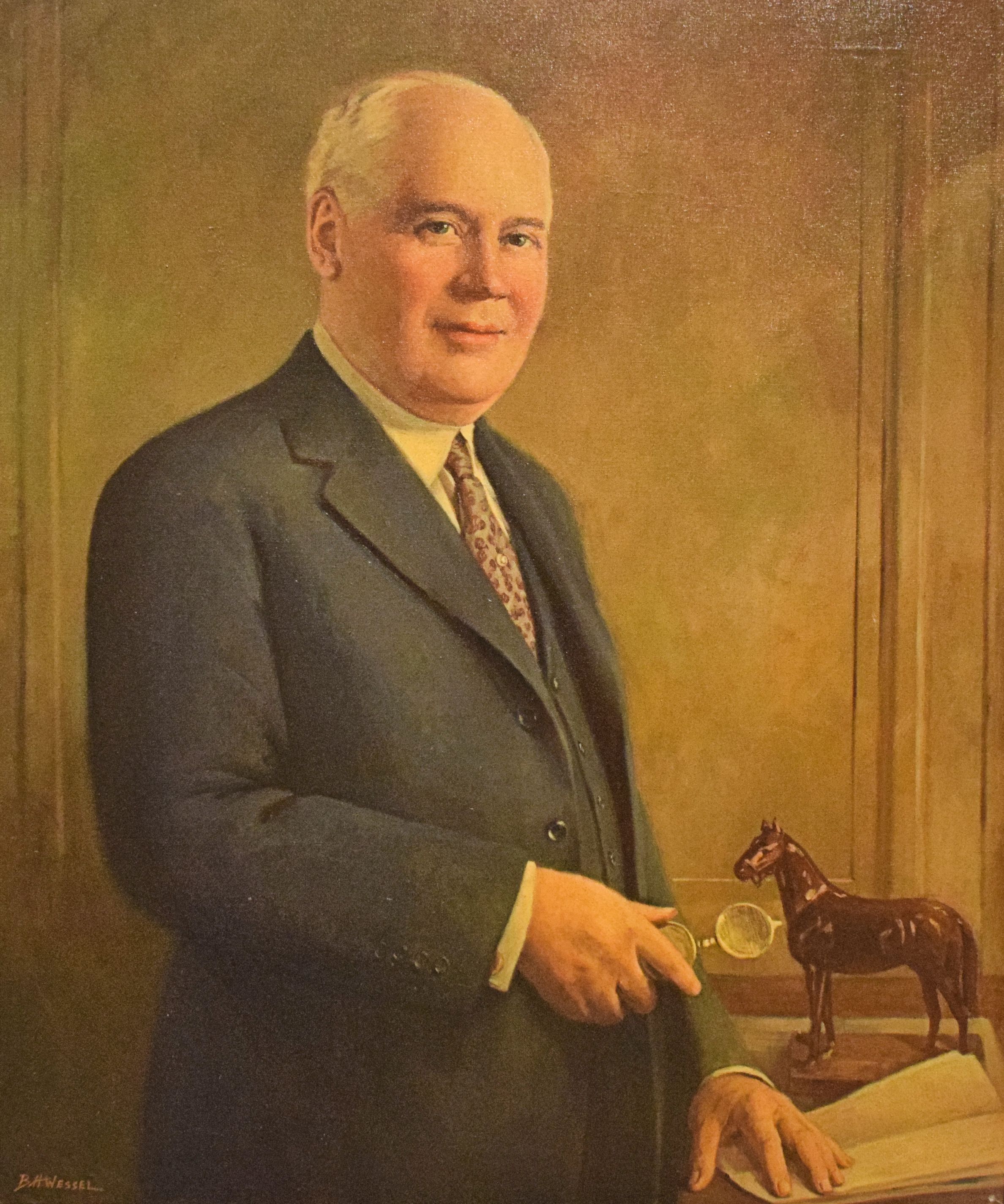

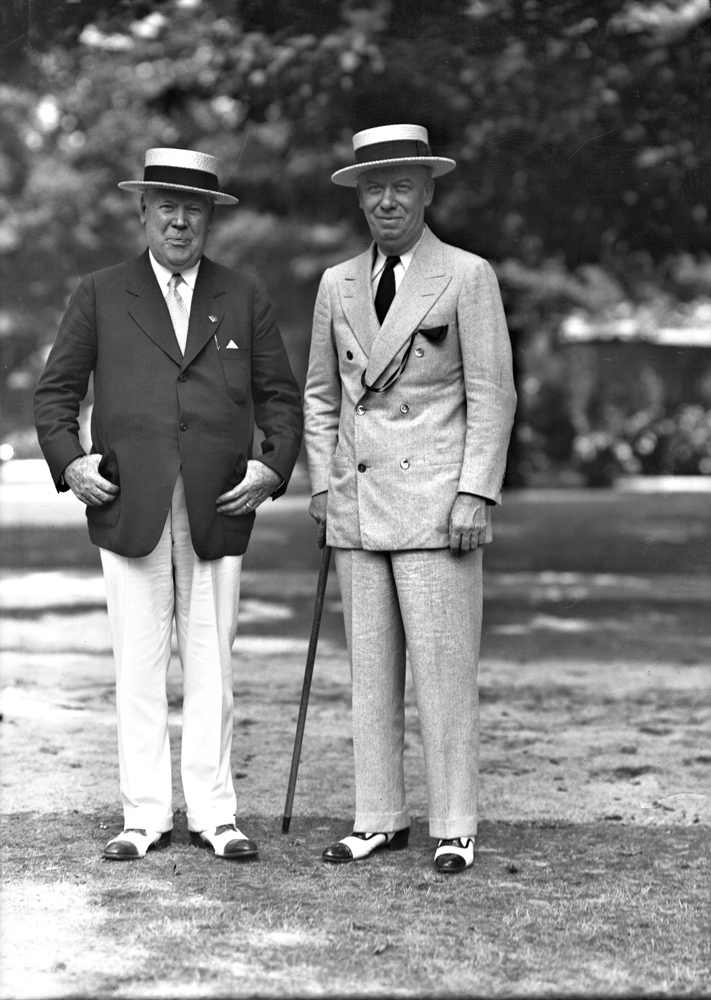

Matt Winn

A 14-year-old Louisville native named Martin J. Winn was among the crowd estimated at 10,000 when Aristides defeated 14 rivals on May 17, 1875, at Churchill Downs in the inaugural running of the Kentucky Derby. In the years that followed, Martin J. Winn became better known as Col. Matt Winn and the Kentucky Derby was transformed from a local event into America’s signature thoroughbred race. Much of the credit for the event’s development belongs to Winn, who saw every Derby in person from the first edition through Ponder’s victory 75 years later in 1949.

2017

June 30, 1861, Louisville, Kentucky

Oct. 6, 1949, Louisville, Kentucky

Biography

A 14-year-old Louisville native named Martin J. Winn was among the crowd estimated at 10,000 when Aristides defeated 14 rivals on May 17, 1875, at Churchill Downs in the inaugural running of the Kentucky Derby. In the years that followed, Martin J. Winn became better known as Col. Matt Winn and the Kentucky Derby was transformed from a local event into America’s signature thoroughbred race. Much of the credit for the event’s development belongs to Winn, who saw every Derby in person from the first edition through Ponder’s victory 75 years later in 1949.

Born on June 30, 1861, Winn became enamored with racing when his father brought him to the first Kentucky Derby. A successful businessman in Louisville, Winn came to the rescue of Churchill Downs when the track was struggling financially in 1902. Leading a syndicate of investors, Winn purchased Churchill for $40,000 and set it on a path toward prosperity and national recognition.

A renowned marketer, Winn made immediate improvements to the track and grounds. The clubhouse also underwent a major renovation, which cost $20,000, an astronomical figure at the time. Behind Winn’s strong leadership and promotion, Churchill realized its first annual profit in 1903.

Winn was instrumental in transitioning Churchill’s wagering system from bookmaking into the pari-mutuel model. In 1908, Louisville city officials began enforcing an anti-bookmaking law that threatened the viability of the track, so Winn quickly moved to install French pari-mutuel machines to handle betting. They were immediately popular with the track patrons and more were soon added. By 1914, pari-mutuel machines were also installed at Latonia, Lexington, Douglas Park, Laurel and all Canadian tracks. In subsequent years, pari-mutuels replaced bookmakers at all American tracks.

In 1911, Winn dramatically changed racing by introducing the $2 minimum bet; in the past, the minimum pari-mutuel bet had been $5, beyond the feasibility of most working people. Winn also saw the new economic power of women and desired to make Churchill Downs and the Derby interesting to them, too. He began the practice of inviting — and using money to lure — celebrities, male and female, to the Derby and publicizing their attendance.

Churchill’s finances steadily improved under Winn, who in 1915, convinced prominent owner Harry Payne Whitney to bring his New Jersey-bred filly Regret to the Kentucky Derby. The recruiting effort paid off handsomely, as the national publicity surrounding Regret’s victory stamped the Derby as a marquee event on the American racing calendar. In recognition of his achievements, Winn was named an honorary Kentucky Colonel.

“He was a showman and sold the Derby, but he cared for it, too,” said Brownie Leach, Winn’s public relations director in an article published in Sports Illustrated. “His major concern for the Derby was making it bigger year by year and having nice people come to it.”

Winn was also an early proponent of radio. At a time when other sports executives believed broadcasts would cut into ticket revenue, Winn embraced the power of radio, believing it had the ability to further advance the Derby as a national spectacle. In 1925, Westinghouse, owner of America’s first commercial radio station, broadcast the Derby, the first horse race to receive a national radio audience. A sizeable uptick in the Derby’s popularity followed.

Winn later pushed for a concrete structure in the Triple Crown series. Working with the executives at Pimlico and Race Course and Belmont Park, he helped implement a formal schedule for the American classics. The Derby was slotted for the first Saturday in May, the Preakness two Saturdays later and the Belmont three Saturdays after that. With annual positions for the races entrenched, all the pieces had fallen into place for the Triple Crown series as we know it today. The popularity of the races grew immeasurably as a result of the stability and organization of the series.

Winn worked at several other tracks in an executive capacity in addition to Churchill, including Latonia, Laurel, Lincoln Fields, Lexington, Empire City and Douglas Park. In 1909, Winn and some partners opened a track in Juarez, Mexico, which succeeded for several years despite Mexican bandits occasionally spraying the track with gunfire. Legendary trainers Max Hirsch and Ben Jones were among those who sent horses to race at Juarez. Despite the civil unrest in Mexico at the time, Winn kept the peace at the track for the most part because of an alliance he formed with the infamous Pancho Villa. A regular guest of Winn’s at the track, Villa, a powerful revolutionary leader, made certain his guerilla fighters steered clear of raiding the Juarez facility out of his respect for Col. Winn. By 1917, however, the fighting and instability in the region led to the track being abandoned.

Winn was never afraid to buck the system. Dissatisfied with Churchill’s racing dates, he took on the Western Turf Association in Kentucky. He later joined forces in New York with James Butler and did the same thing on behalf of Empire City, this time battling The Jockey Club. Winn prevailed both times. Asked by the United States government to suspend the Kentucky Derby in 1943 because of World War II, Winn refused. That year, Count Fleet won the Derby and went on to sweep the Preakness and Belmont to become America’s sixth Triple Crown winner.

Winn’s final project was an attempt to re-charter Churchill Downs as a non-profit corporation with the proceeds to benefit the University of Louisville Medical School. The concept, however, passed with Winn and was never resurrected.

William H. P. Robertson in “The History of Thoroughbred Racing in America” said Winn was “a Moses who led the sport through trying times.”

Winn was The Thoroughbred Club of America’s Honored Guest in 1943. The Matt Winn Stakes at Churchill Downs is named in his honor.

A 1949 New York Times article said of Winn’s influence on the Kentucky Derby, “He alone made it what it is today.”

Winn died on Oct. 6, 1949 at the age of 88 and was buried in St. Louis Cemetery in Louisville.

Media