Abe Hawkins

Abe Hawkins lived a life that was extraordinary, tragic, and mysterious. One of the most talented and accomplished American athletes both before and in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Hawkins was revered for his exceptional skills as a jockey. He won major events, set records, received praise in the press, and had his innovative riding style popularized by jockeys of subsequent generations.

2024

unknown

May 27, 1867

Biography

Abe Hawkins lived a life that was extraordinary, tragic, and mysterious. One of the most talented and accomplished American athletes both before and in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Hawkins was revered for his exceptional skills as a jockey. He won major events, set records, received praise in the press, and had his innovative riding style popularized by jockeys of subsequent generations.

Those triumphs and glories, however, were juxtaposed against a difficult and sad reality — Hawkins was an enslaved person for much of his life and there are numerous gaps in his story. Many of his most celebrated achievements as a jockey occurred while he was the property of wealthy southern slaveholder Duncan F. Kenner, one of the most prominent breeders and owners of racehorses in the country.

Little is known about Hawkins other than his athletic accomplishments. The date and location of his birth has never been discovered and there are no records about his family or even his last name. Who were his parents? Did he have any siblings? It is unlikely those questions will ever be answered. It is also unknown if Hawkins ever married or had children. When he became a rider in the early 1850s, he was referred to simply as “Abe” or “Old Abe.”

Hawkins was initially mentioned in press accounts at the Metairie Course in New Orleans in 1851. He was praised for his talent, intelligence, and honesty. Hawkins had developed into one of the best in the sport by the time he etched his name into history at Metairie in April 1854. The legacy-defining event for Hawkins came shortly after he was purchased by Kenner for the considerable sum of $2,300, a transaction that was reported in the papers alongside livestock sales.

Northern Louisiana horseman Gen. T. J. Wells entered his horse Lecomte in a $2,000 Jockey Club purse, which also featured the mighty Lexington. Both Lecomte and Lexington were sons of the prolific stallion Boston. Lexington was undefeated at the time and generally considered peerless. A week earlier, he easily defeated Lecomte in the Great State Post Stakes. Lecomte’s trainer, an enslaved person known only as Hark, convinced Wells to use Kenner’s jockey against Lexington, reportedly saying, “If you can get Abe to ride Lecomte he will beat Lexington certain.”

With Hawkins aboard, riding at 89 pounds, Lecomte shockingly defeated Lexington in consecutive four-mile heats. In winning the first heat by six lengths, Lecomte completed the distance in 7:26. The dazzling time was more than six seconds faster than the previous standard set by Hall of Fame member Fashion a dozen years earlier. Lecomte finalized the victory in the second heat with a four-length score in 7:38¾. It was the only defeat of Lexington’s career.

Hawkins continued to win with regularity at Metairie that spring. Another of his notable victories was with Kenner’s colt Arrow in a $1,000 Jockey Club purse. With Hawkins up, Arrow set the best time on record at the three-mile distance with heat times of 5:36½ and 5:34, respectively.

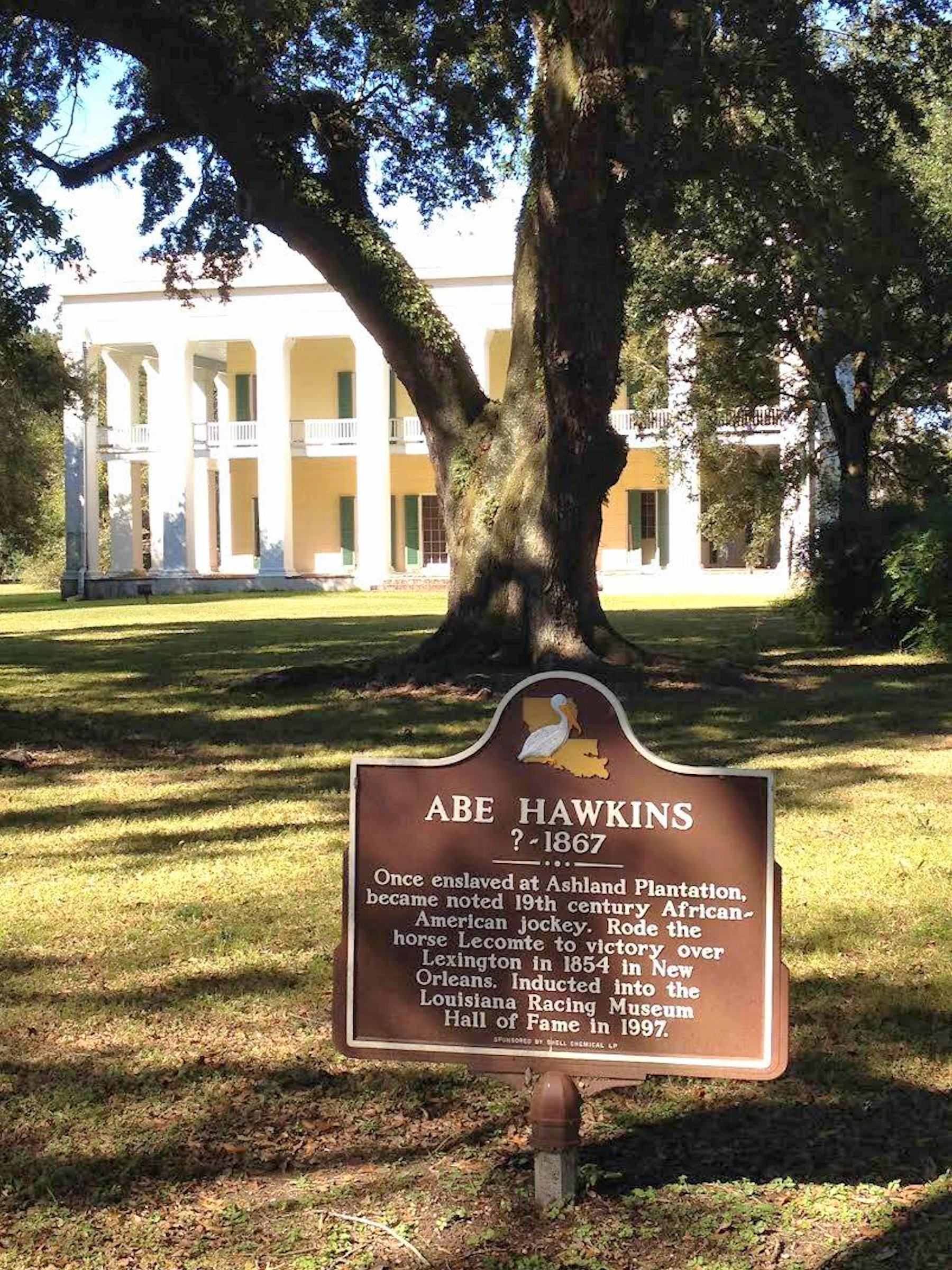

For the next decade, Hawkins rode with distinction while enslaved at Ashland, the Louisiana plantation owned by Kenner. Various contemporary reports assert Kenner kept hundreds of slaves at Ashland and other plantations he owned throughout the state. Ashland was a sugarcane operation and thoroughbred nursery that also featured a training track for Kenner’s racing stable. Involved in Louisiana and Confederate States of America politics, Kenner also had an ownership stake in Metairie and was a founding member of the Louisiana Jockey Club.

Wearing Kenner’s colors of red jacket and cap, Hawkins was a major reason his owner’s racing stable was “acknowledged to be the strongest in the South,” according to an 1859 Spirit of the Times article. Among the top horses Hawkins rode to victory for Kenner were the undefeated colt Whale and the standout filly Minnehaha, who was said to be “the pet of Louisiana … believed to be the fastest nag in the world,” according to Spirit. With Whale and Minnehaha each winning twice at the 1858-59 Metairie winter meeting, the New Orleans Daily Picayune stated, “We cannot omit the admirable manner in which Mr. Kenner’s horses are brought out. With Graves to train, Abe to ride … Duncan F. Kenner is truly hard to beat.”

With his victory against Lexington and the continued success that followed, Hawkins became known in the press as “The Black Prince,” “The Dark Sage of Louisiana,” and “The Slayer of Lexington.” He was arguably the most famous and successful jockey in America prior to Isaac Murphy, as well as the first Black athlete to gain national notoriety.

The Civil War and Emancipation Proclamation gave Hawkins his liberation. The Union Army seized New Orleans in the spring of 1862, confiscating much of Kenner’s property and freeing his slaves. Hawkins made his way north for riding opportunities and won a documented 25 races from 1864 through 1866. During this time, Hawkins furthered his remarkable reputation and reportedly made good money, particularly at Saratoga Race Course, Jerome Park, and the course at Paterson, New Jersey.

In 1866, while riding for Woodburn Farm’s R. A. Alexander, Hawkins won the third running of the Travers Stakes and the second Jersey Derby aboard Merrill (trained by Hall of Famer and former slave Ansel Williamson). He also took the inaugural Jerome Stakes with Watson (for Hall of Fame trainer Jacob Pincus). The year prior, he won the first Jersey Derby aboard Richmond for owner Oden Bowie, who later became Maryland’s governor.

Kenner, meanwhile, regained his land after the war in the early days of Reconstruction. He invited Hawkins to return at Ashland as a free man, which he did late in the fall of 1866. Hawkins rode for Kenner during Metairie’s races that December, but by the following May, Turf, Field and Farm reported the jockey’s death following an illness.

“As a rider and a jockey he had no equal in this country … Good riders and strictly honest ones are rare; therefore, the death of Old Abe is an irreparable loss to the American turf.”

Hawkins, however, was not dead. Days after his obituary was published, Hawkins read of his own demise in the St. Louis Republican. After a brief recuperation, he felt well enough to travel to Cincinnati with plans to ride in the Buckeye Jockey Club’s spring meet. Unfortunately, his illness returned and Hawkins was unable to rally a second time. Old Abe died of consumption on May 27, 1867, and his body was shipped back to Ashland. Kenner buried him, not in the property’s slave cemetery, but in a brick tomb under a live oak tree that overlooked the plantation’s training track.

In its second obituary of the great rider, Turf, Field and Farm said of Hawkins, “It would appear that in the first heat of his contest with Death, Old Abe successfully jockeyed his formidable opponent, but in the second heat he was distanced by the grim phantom. Peace to his weary old bones.”

Hawkins was gone, but his legacy as arguably the premier jockey of his time lived on. His riding techniques — making use of short stirrups and a crouching posture — later came to be known as the “American seat.” Later in the 19th century, Hall of Fame jockeys Willie Simms and Tod Sloan notably utilized the methods Hawkins introduced decades earlier.

Media