Man o' War (KY)

The 1920s are considered a golden age for sports heroes in America. Babe Ruth emerged as a cultural icon on the baseball diamond, swatting prodigious home runs and making World Series victories a rite of passage for the New York Yankees. In the prize ring, Jack Dempsey was pulverizing opponents as heavyweight champion of the world while gaining the adoration of countless fans. The gridiron could boast of Red Grange, the “Galloping Ghost” who established himself as the National Football League’s first superstar and was the key figure in the pro game realizing acceptance in mainstream America. However, at the dawn of the 1920s, no athlete in the land was more revered than horse racing’s greatest marvel, the mighty Man o’ War. Ruth had charisma. Dempsey had power. Grange had speed. Man o’ War had all of those attributes. But instead of being a galloping ghost, Man o’ War was an equine freight train.

Racing Record

21

Starts

| 1919 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 0 | $83325 $83,325 |

| 1920 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | $166140 $166,140 |

Biography

The 1920s are considered a golden age for sports heroes in America. Babe Ruth emerged as a cultural icon on the baseball diamond, swatting prodigious home runs and making World Series victories a rite of passage for the New York Yankees. In the prize ring, Jack Dempsey was pulverizing opponents as heavyweight champion of the world while gaining the adoration of countless fans. The gridiron could boast of Red Grange, the “Galloping Ghost” who established himself as the National Football League’s first superstar and was the key figure in the pro game realizing acceptance in mainstream America. However, at the dawn of the 1920s, no athlete in the land was more revered than horse racing’s greatest marvel, the mighty Man o’ War. Ruth had charisma. Dempsey had power. Grange had speed. Man o’ War had all of those attributes. But instead of being a galloping ghost, Man o’ War was an equine freight train.

In 1920, Man o’ War won all 11 of his starts to conclude a two-year run in which he won 20 of 21 starts and compiled an all-time earnings record of $249,465. When all was said and done, Man o’ War had established three world records, two American records, seven track records, and equaled another track standard.

Man o’ War was a star everywhere he went, especially at Saratoga, where he thrived in the summers of 1919 and 1920. The Spa was the stage on which Man o’ War delivered some of his most breathtaking performances. It was also the place he suffered his lone defeat, an event that is still regarded as one of the most controversial in the sport’s history.

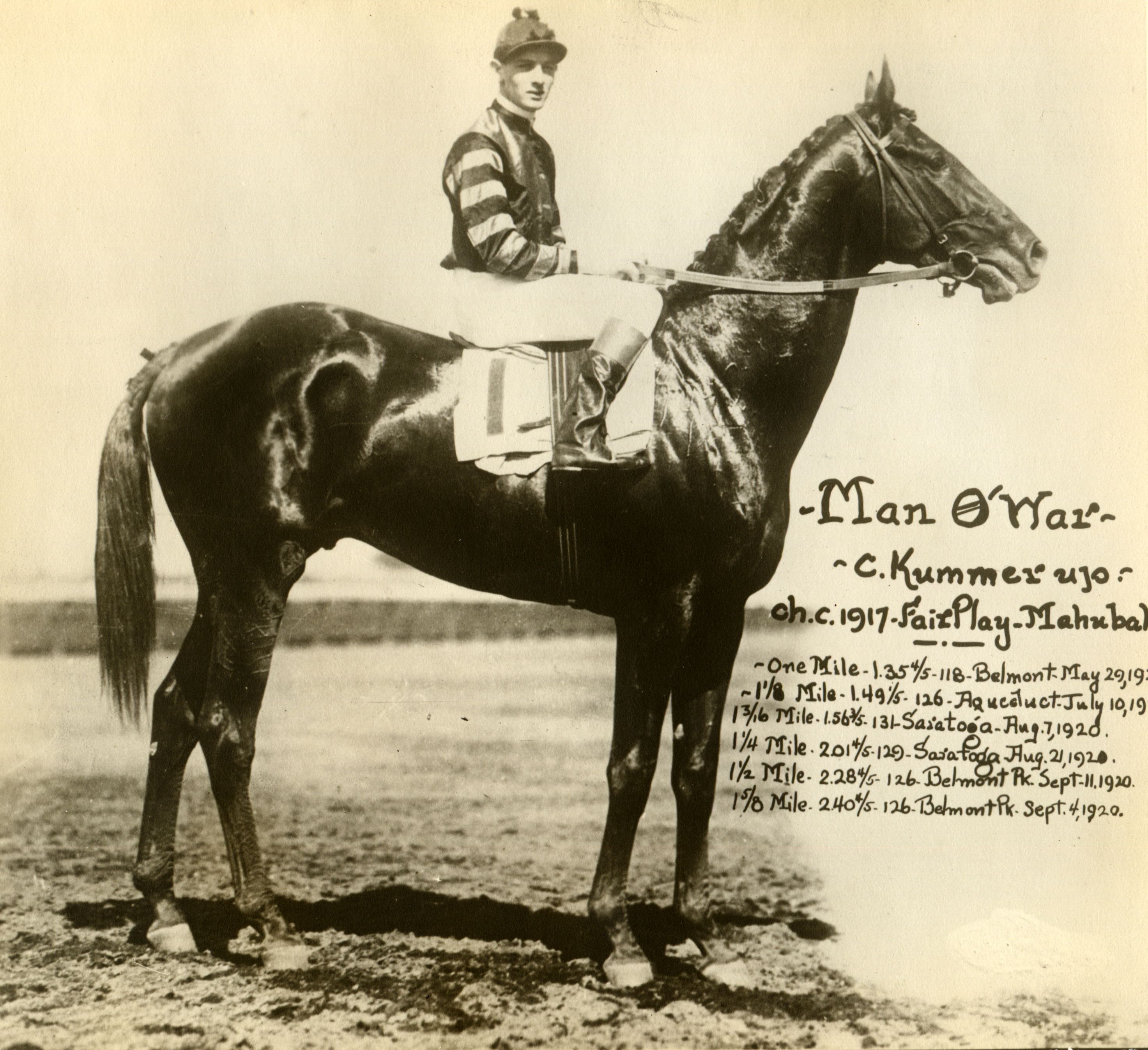

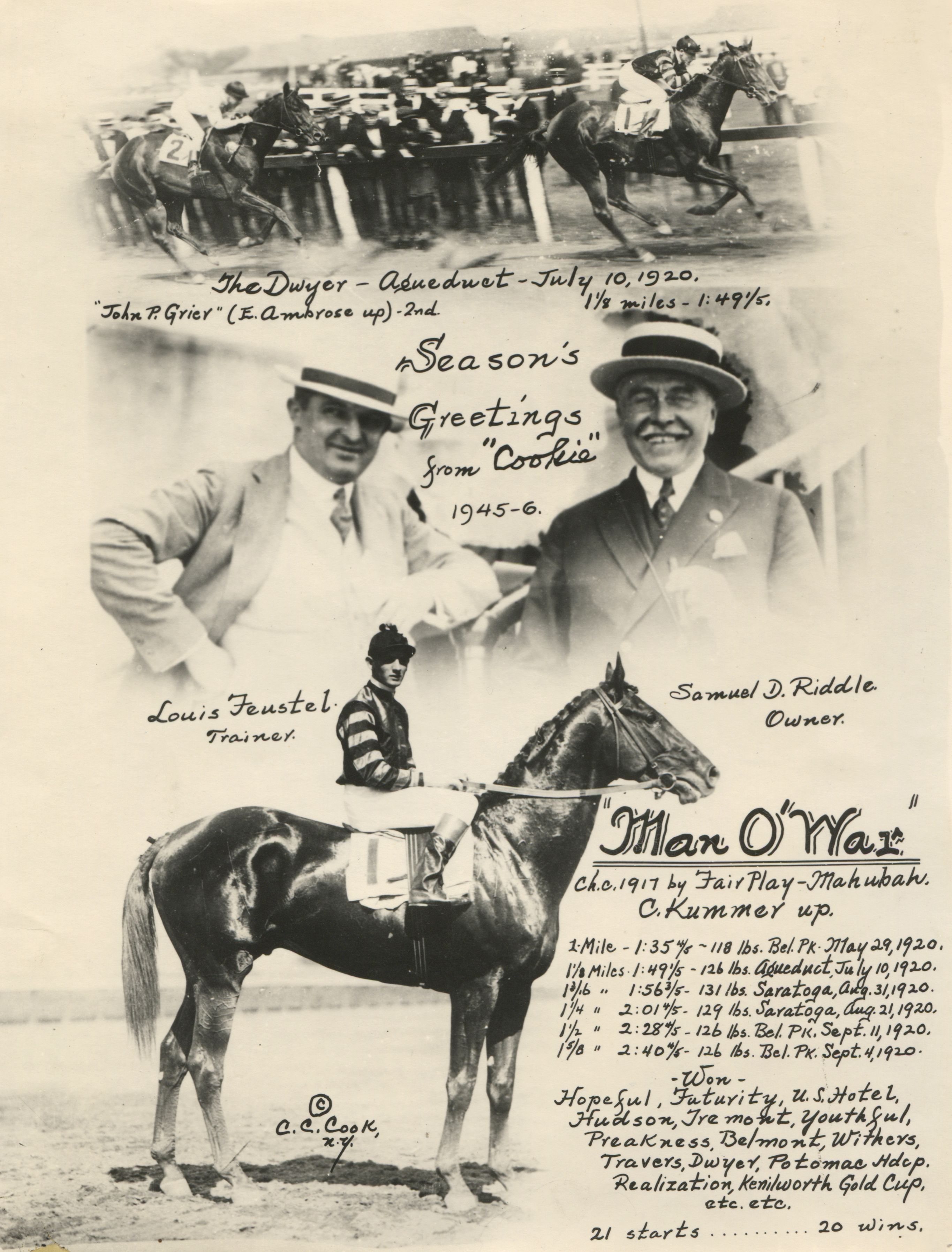

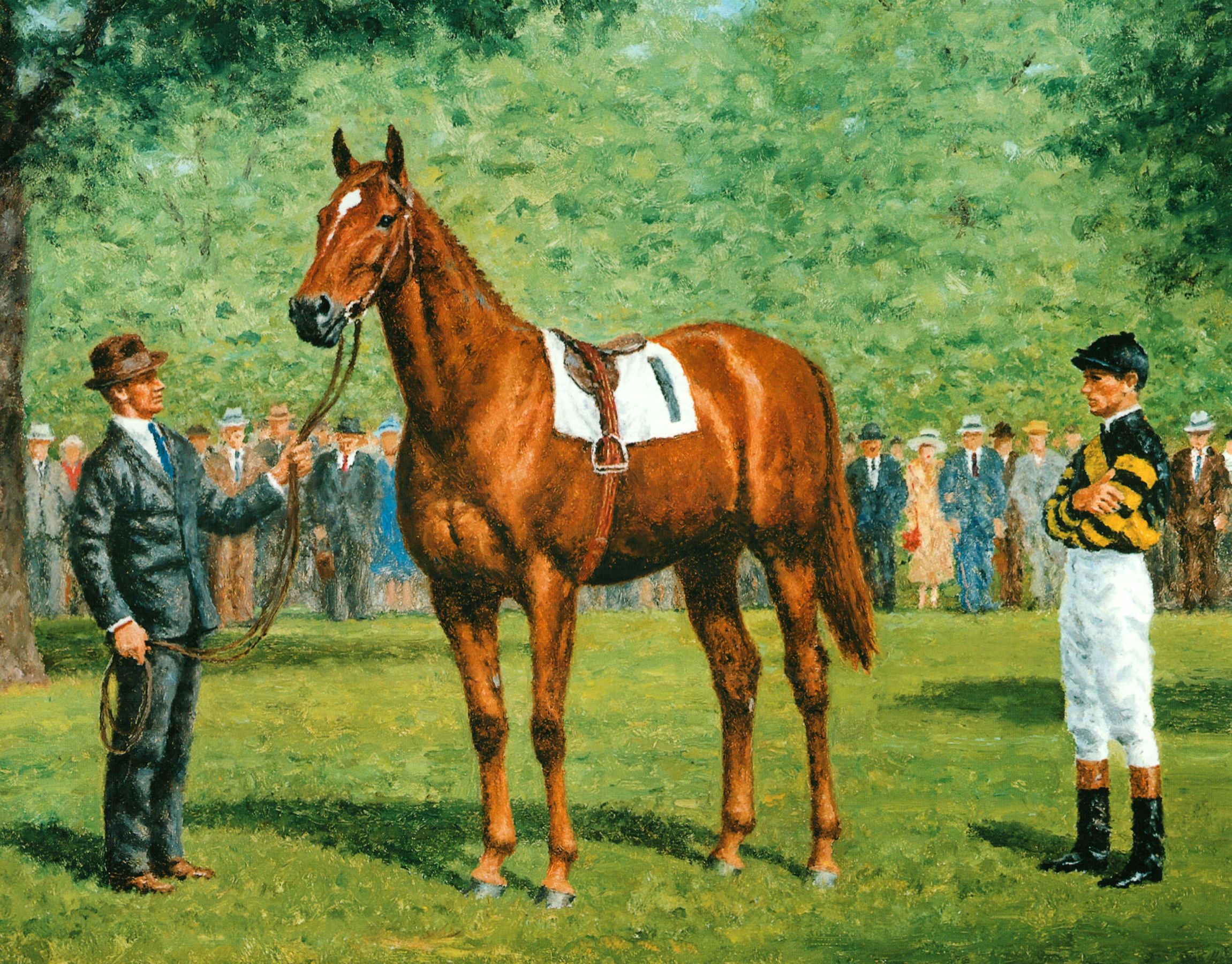

Bred by August Belmont II, Man o’ War was foaled on March 29, 1917, at Nursery Stud near Lexington, Kentucky. He was blessed with quality bloodlines, as his sire, Fair Play, was a Hall of Famer. His dam, Mahubah, was well thought of in breeding circles even though she was never a star on the track. Man o’ War’s paternal grandfather was the ill-tempered 1896 Belmont Stakes winner Hastings, a violent competitor known to bite and ram other horses during races. His maternal grandfather was English Triple Crown winner Rock Sand.

Belmont’s military involvement in World War I prompted him to sell his entire 1917 yearling crop. Avid sportsman Samuel Riddle, a Pennsylvania textile manufacturer, purchased Man o’ War for $5,000 on the advice of Hall of Fame trainer Louis Feustel at Saratoga’s 1918 yearling sales in what turned out to be one of the greatest bargains in racing history.

Like his grandfather, Man o’ War had a violent disposition, forcing Feustel to bring him along slowly in training. Man o’ War routinely dumped his exercise riders and was usually belligerent when his handlers attempted to saddle him.

“He fought like a tiger,” Riddle once said in describing his stable’s early experiences with Man o’ War. “He screamed with rage and fought us so hard that it took several days before he could be handled with safety.”

One Saratoga story describes Man o’ War enjoying “more than 15 minutes of freedom after launching his rider more than 40 feet” during a morning workout.

After cooling his temper to a manageable level and settling into training, Man o’ War made a stunning debut in a maiden race against six other 2-year-olds at Belmont Park on June 6, 1919. Despite having jockey Johnny Loftus using much restraint throughout the race, Man o’ War won by an easy six lengths and made quite an impression in the papers.

“He made half-a-dozen high-class youngsters look like $200 horses,” wrote the turf editor of the New York Morning Telegraph.

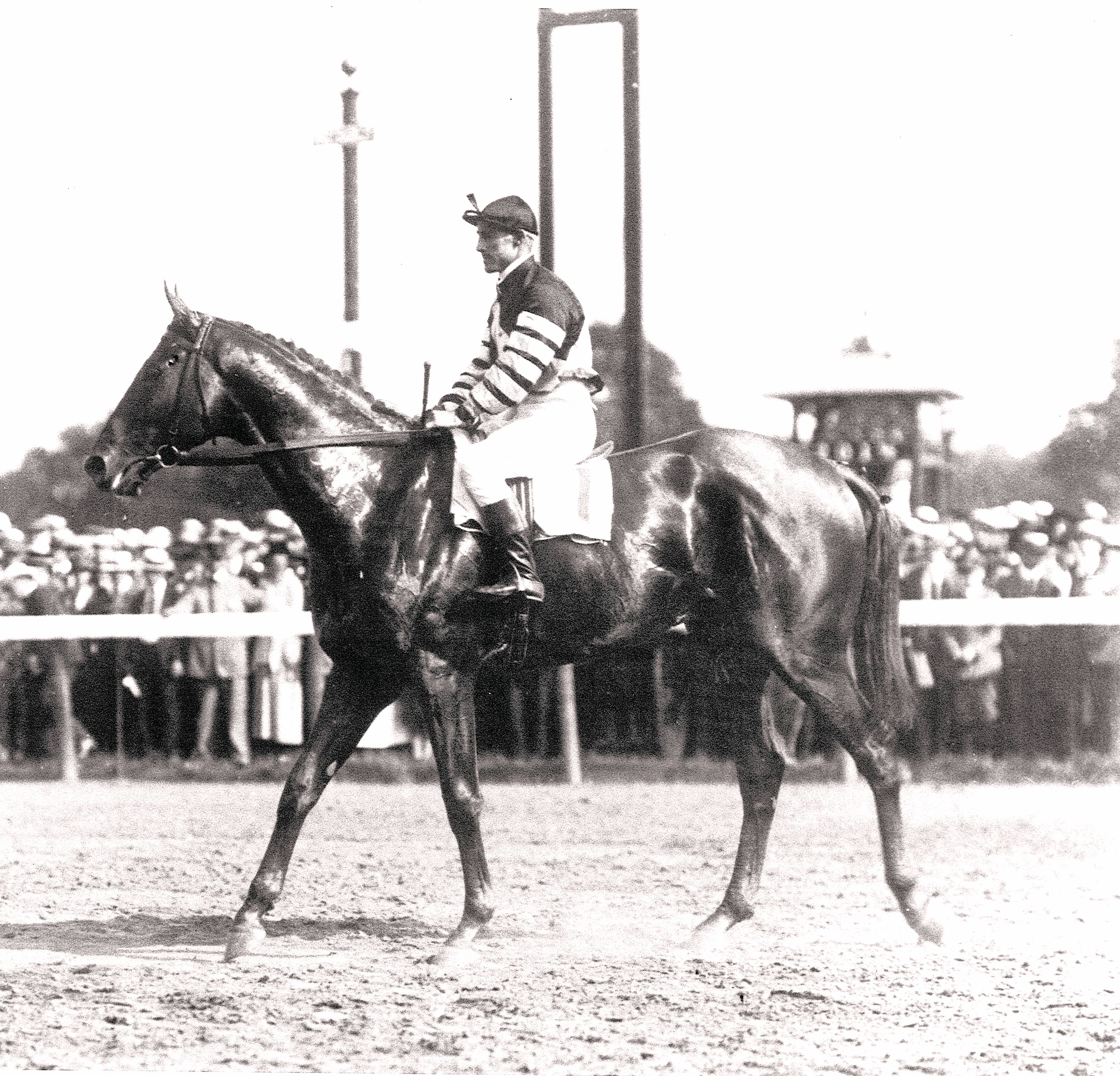

With his power, blazing speed, and incredible 28-foot stride (believed to be the longest ever), Man o’ War captivated the imagination of racing fans and drew record crowds everywhere he appeared. He was the favorite in every one of his races and three times he was recorded to have odds of 1-100

Man o’ War became such a sensation that police officers and Pinkerton guards had to protect him at the tracks from souvenir hunters who routinely attempted to snatch the hairs from his mane and tail. His notoriety also attracted more significant danger, as Riddle became aware of multiple assassination plots against his great runner. Riddle went to great lengths to protect Man o’ War. Armed guards were always around his stall and even Feustel had personal security.

The infusion of popularity Man o’ War brought to thoroughbred racing could not have come at a more opportune time for the sport. Racing had been banned in New York in 1911 and 1912 because of anti-gambling legislation led by Gov. Charles Hughes. Several other states took up the crusade and most of the prominent stables either folded or moved to Europe.

New York racing regained its legal status in 1913, but soon the nation’s focus shifted to World War I. Track attendance and racing purses had plummeted significantly before Man o’ War rejuvenated the sport.

Man o’ War’s presence made the turnstiles swing at dizzying rates for his Saratoga appearances. He romped in his Spa debut in the United States Hotel Stakes on Aug. 2, 1919, and decimated the competition in the Grand Union Hotel Stakes and the Hopeful that summer. In his official Daily Racing Form past performances, the descriptions of Man o’ War’s victories in those races are “Eased in final 16th” in both the U.S. Hotel and Grand Union Hotel and “Easily” in the Hopeful, a testament to the superiority he displayed.

The summer of 1919 was not without controversy for Man o’ War. What transpired on Aug. 13 that year at Saratoga in the Sanford Memorial turned out to be the one blemish on an otherwise flawless record. For the first and only time, Man o’ War was defeated. The loss, however, did little to tarnish Man o’ War’s reputation. If anything, it enhanced his legend, as he almost pulled off a miracle victory. The circumstances of the race remain shrouded in mystery and controversy. The horse that handed Man o’ War his only defeat was the aptly named Upset.

The blame has often been assigned to the man who was filling in that day for Mars Cassidy, the regular race starter. The substitute, Charles H. Pettingill, was in his late 70s and reportedly had problems with his vision. Years earlier, Pettingill almost incited a riot in Chicago when he kept the horses at the start of the American Derby for an hour and a half, forcing the race to be restarted almost 40 times. Horses in Man o' War's era broke from a piece of webbing that was strung across the track, as the starting gate had not yet been introduced. Man o’ War, always eager to get on with the race, was infamous for breaking prematurely through the barrier. On the day of the Sanford, he broke through five times, each time having to be pulled up.

Loftus was backing up Man o’ War, trying to line him up again after his fifth lunge through the tape. Without warning, Pettingill sprang the webbing, apparently catching Loftus by surprise. Various reports said Man o’ War was facing the wrong way, sideways, or simply caught off guard and unprepared for the start. Whatever position he was in, Man o’ War was left at the start and at a clear disadvantage.

Man o’ War made a furious rally to get in contention. Loftus attempted to get through on the rail approaching the stretch, but he found traffic trouble and became locked in a pocket. Past the eighth pole, Loftus swung his mount outside and Man o’ War lost valuable ground.

"Man o’ War was abominably ridden," The Thoroughbred Record reported.

Although he was left at the start, buried in traffic for part of the journey, and forced wide, Man o’ War still nearly won the race. The result was Upset winning by a diminishing half length. Man o’ War blew past Upset right after the finish line.

The shocking result became even more mysterious the next year when The Jockey Club refused licenses to both Loftus and Upset’s rider, Willie Knapp. No explanation was provided, but both jockeys were never allowed to ride again. Was there a conspiracy between the riders? If so, it has never been uncovered. Based on his dominant past performances, Man o’ War was also forced to carry 15 more pounds than Upset in the Sanford.

“Given an equal chance Man o’ War would undoubtedly have won the race,” The Saratogian stated.

The Sanford Memorial, however, proved to be a fluke. Man o’ War raced against Upset six other times and won each meeting. Man o’ War had no trouble bouncing back from the Sanford. He followed his lone defeat with the victories in the Grand Union Hotel and Hopeful at Saratoga before closing out his juvenile campaign with an easy score in the Futurity at Belmont.

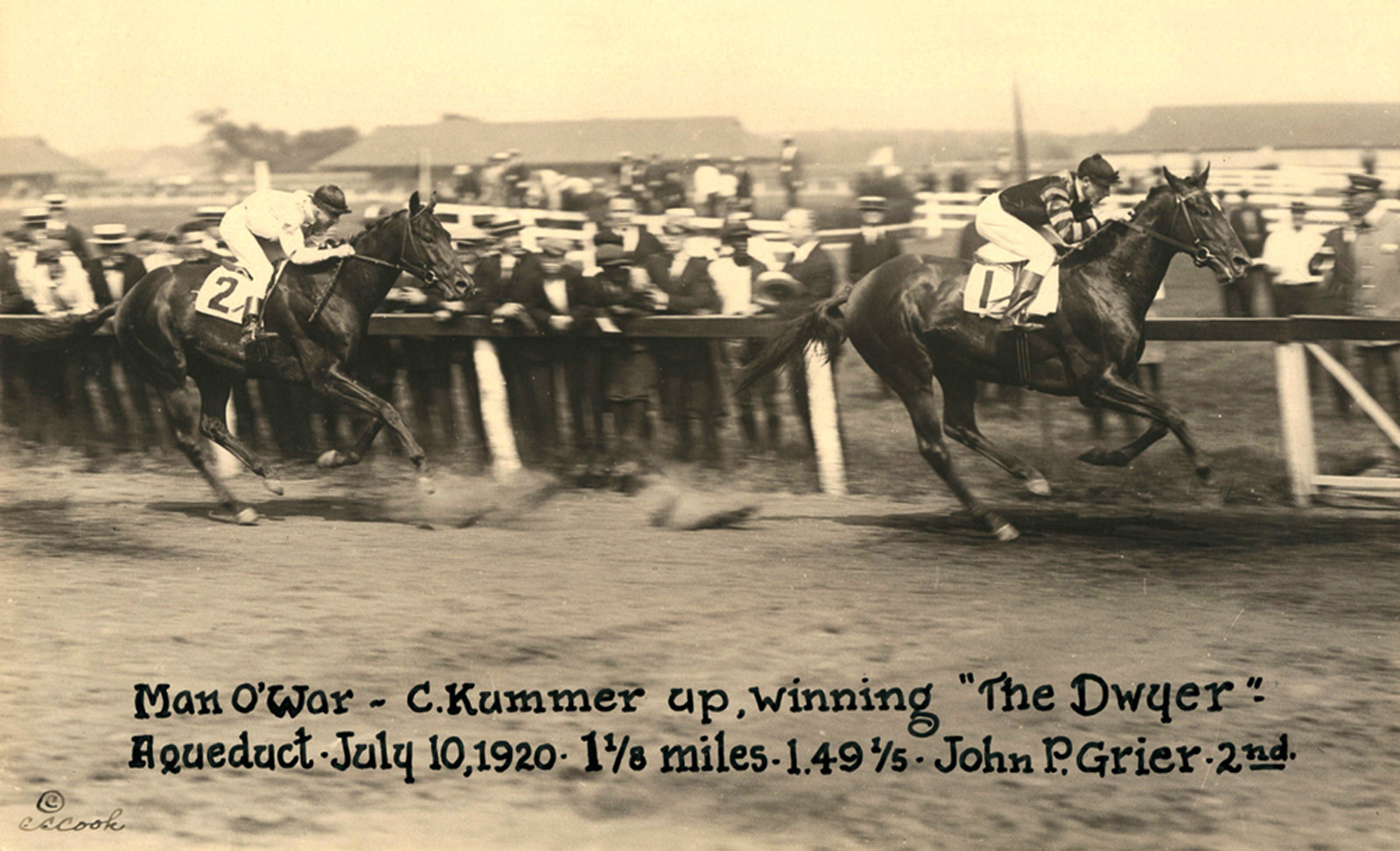

With Loftus exiled by The Jockey Club, Riddle and Feustel chose Clarence Kummer as Man o’ War’s new rider and the combination proved to be a winning one. Riddle decided to pass on the Kentucky Derby in favor of having Man o’ War make his 3-year-old debut in the Preakness. Man o’ War won easily, as he did in the Withers, Belmont (a 20-length victory), Stuyvesant, and Dwyer.

Man o’ War returned to Saratoga in August 1920 and romped in the Miller Stakes. He followed with a remarkable performance in the Travers. Andy Schuttinger substituted for the injured Kummer in the Midsummer Derby and Man o’ War did not skip a beat. Even though he was restrained in the stretch, Man o’ War covered the 1¼-mile distance in 2:01⅘, setting a stakes and track record that stood for 42 years.

After winning the Travers, Man o’ War returned to Belmont for the Lawrence Realization. By this time few owners had any interest in racing against Riddle’s powerhouse. Only Hoodwink, at 100-1 odds, came forward to meet Man o’ War. Knowing Hoodwink provided no legitimate threat, Kummer set Man o’ War against the clock. The mighty colt responded by shattering the previous world record for 1⅝ miles (2:45 flat) by more than four seconds (2:40⅘). Poor Hoodwink was left in the dust by an approximate 100 lengths even though the official race chart said Man o’ War was restrained at the end and never fully extended. Man o’ War’s performance that day stood as the Belmont record for the distance for 98 years until surpassed by Rocketry in 2018.

Following the Lawrence Realization, Man o’ War pushed his win streak to 13 with impressive victories in the Jockey Club Gold Cup and Potomac Handicap. At this point, there appeared to be no competition for Man o’ War — with one possible exception, Sir Barton, the sport’s first Triple Crown winner in 1919.

Riddle sent Man o’ War to Kenilworth Park in Canada in October of 1920 for a match race against Sir Barton. There was tremendous excitement for the showdown, but the result was familiar and predictable. Sir Barton broke well and owned an early lead, but Man o’ War quickly reeled him in and cruised to a seven-length victory and smashed the track record for 1¼ miles. Again, Kummer restrained his mount throughout the contest.

There was nothing left to prove. Man o’ War was a perfect 11-for-11 as a 3-year-old and had won 14 in a row. He had carried as much as 138 pounds as a sophomore and as much as 130 pounds six times as a juvenile. What could be next? There was talk of sending Man o’ War to England for the Ascot Gold Cup. Matt Winn telegraphed an offer from Churchill Downs for a match race with the great gelding Exterminator. The Chicago World’s Fair wanted Man o’ War as a drawing card. There were even offers to make him a movie star.

Riddle’s decision was made easy by the handicapper for The Jockey Club, Walter S. Vosburgh, who assigned the weights horses carried in New York. Riddle asked Vosburgh what weight he would put on Man o’ War if he were to race at age 4. Vosburgh told him it would be the highest weight ever carried, as much as 150 pounds.

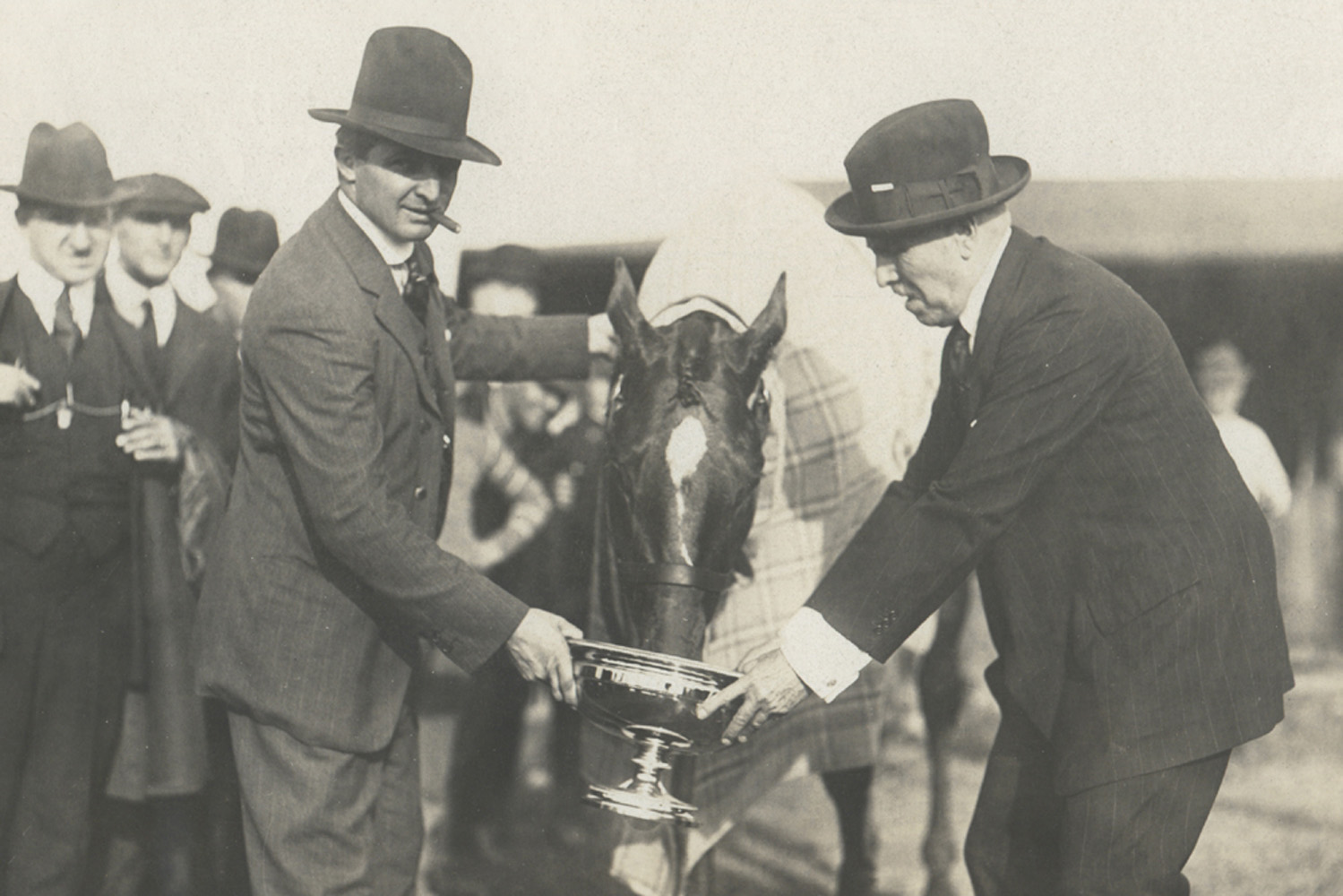

Man o’ War’s days of dazzling on the track were through. Rather than run under the extreme weight, Riddle opted to retire Big Red after his 3-year-old campaign. At the time of Man o’ War’s retirement, Riddle was offered $1 million for the horse. He turned it down. It wasn’t until 35 years later that any thoroughbred was sold for that amount.

Although Man o’ War never raced in Kentucky, he spent most his life in the Bluegrass State. There are estimates that as many as three million visitors traveled to Riddle’s Faraway Farm between 1921 and 1947 to see the legendary horse in retirement and hear his groom, Will Harbut, tell glorious tales of his exploits on the track. Harbut became famous for the way he crafted the stories of Man o’ War, and he always introduced his charge to visitors as “the mostest horse that ever was.”

Harbut’s descriptions of Man o’ War thrilled visitors from all walks of life. He would begin by escorting guests around the barns, introducing them to Riddle’s other distinguished horses. He would show them the antique fire bell that was rung whenever a horse raised on the farm won a stakes race. But all these were mere preliminaries. Everyone knew what was coming. Finally, Harbut would arrive at Man o’ War’s stall and the visitors became entranced as the great horse was led out. Great Britain’s ambassador to the United States, Lord Halifax, once visited the farm to see Man o' War and was captivated by Harbut’s storytelling.

“That was worth coming halfway around the world to hear,” Lord Halifax said admiringly.

Man o’ War began experiencing heart trouble in 1943, forcing his retirement from breeding. He died of a heart attack on Nov. 1, 1947, at Faraway, less than a month after Harbut’s death. It required 13 men to lift Man o’ War’s 1,300-pound body from his stall. Three days later, more than 2,000 people attended Man o’ War’s funeral, which was broadcast on NBC Radio and featured nine eulogies. A scroll from the U.S. Army’s First Cavalry Division was placed with a black ribbon on Man o’ War’s barn. The First Cavalry Division had dubbed Man o’ War an honorary colonel. In Japan, an estimated 3,000 members of the country’s cavalry division paid their respects to Man o’ War with military honors as well. American racetracks held a moment of silence at 3 p.m., coinciding with the funeral. At 3:24 p.m. on Nov. 4, 1947, buglers from the Man o’ War Post of the American Legion, dressed in the famous black and yellow Riddle silks, signaled farewell to the legend with the playing of Taps.

Man o’ War was buried at Faraway Farm and a massive bronze statue by Herbert Hazeltine was eventually mounted on a marble base with only the words “MAN O’ WAR” as the inscription. No other words were needed. Three decades later, Man o’ War’s remains were exhumed and moved along with the 3,000-pound statue to the Kentucky Horse Park. Thousands of visitors pay their respects at his resting place each year.

Man o’ War enjoyed tremendous success as a stallion. Among his 386 registered foals, 64 became stakes winners, including his greatest son, 1937 Triple Crown winner and Hall of Fame member War Admiral. He also sired Kentucky Derby winner Clyde Van Dusen, as well as Belmont Stakes winners American Flag and Crusader, a Hall of Famer. Man o’ War also produced Hall of Fame steeplechaser Battleship, winner of the famed British Grand National.

“He was as near to a living flame as horses ever get, and horses get closer to this than anything else. It was that even when he was standing motionless in his stall, with his ears pricked forward, and his eyes focused on something above the horizon which mere people never see, energy still poured from him,” racing writer Joe Palmer said. “He could get in no position which suggested actual repose, and his very stillness was that of a coiled spring, of the crouched tiger.”

Achievements

Champion 2-Year-Old Male — 1919

Horse of the Year — 1920

Champion 3-Year-Old Male — 1920

Triple Crown Highlights

Won the Preakness Stakes — 1920

Won the Belmont Stakes — 1920

Media