Boston (VA)

Long before Man o’ War, Citation, Kelso, or Secretariat arrived on the scene there was an equine sensation by the name of Boston who reigned as the undisputed champion of American thoroughbred racing. In the once and distant era of grueling marathon contests, Boston was in a class of his own.

1955

1833

Timoleon

Sister to Tuckahoe

Balls Florizel

John Wickham

John Wickham

Nathaniel Rives

William R. Johnson

James Long

John Belcher

William R. Johnson

Arthur Taylor

1836-1843

$51,700

Racing Record

45

Starts

| 1836 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | $700 $700 |

| 1837 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | $2000 $2,000 |

| 1838 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | $8900 $8,900 |

| 1839 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 0 | $19300 $19,300 |

| 1840 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | $14700 $14,700 |

| 1841 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | $2900 $2,900 |

| 1842 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | $2400 $2,400 |

| 1843 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | $800 $800 |

Biography

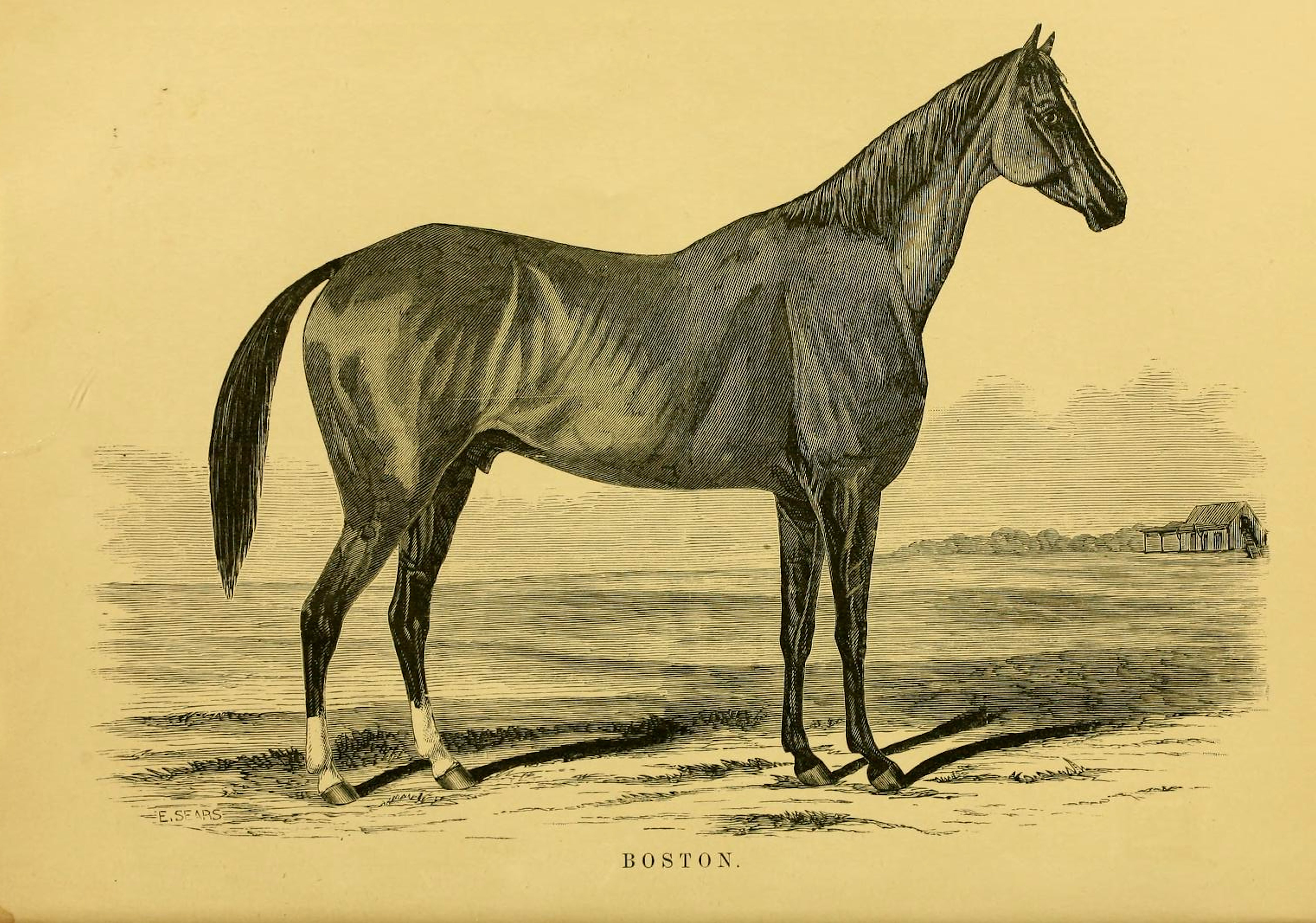

Long before Man o’ War, Citation, Kelso, or Secretariat arrived on the scene there was an equine sensation by the name of Boston who reigned as the undisputed champion of American thoroughbred racing. In the once and distant era of grueling marathon contests, Boston was in a class of his own.

Bred in Virginia by attorney John Wickham, who also initially owned the horse, Boston was lost in a game of cards to Richmond native Nathaniel Rives. Named after a popular card game — not the city — Boston was later known by the moniker of “Old White Nose” because of his blazed face.

To say Boston was difficult to train would be an understatement — evil-tempered would be a more accurate depiction. He regularly threw his exercise riders and on the occasions that didn’t work he would drop to the ground and roll, a tactic that injured a number of would-be passengers. Boston regularly bit humans and other horses, which led one of his early trainers to recommend that Boston be “either castrated or shot, preferably the latter.”

Once he was finally in a formal race, on April 20, 1836, at Broad Rock, Virginia, Boston continued to do things his way. In his first effort, he stopped coldd in the middle of the track and refused to run. Switching tactics, a slave rider named Ned was given the daunting task of breaking Boston. Ned continued to annoy the horse by hooking him up to a cart and having him take people on rides through Richmond and the nearby Virginia countryside in the summer of 1836.

By that fall, Boston had been trained well enough to return to the races, although he always retained his ornery nature. Rives turned Boston over to the Newmarket, Virginia, stable of Col. William R. Johnson, known as the “Napoleon of the Turf.”

With Johnson now as his trainer, Boston developed into the greatest American racehorse of his time. He was undefeated at ages 4 and 5, starting in 15 races, most of which were four-mile heats. Boston dominated his foes in Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Camden, New Jersey, and at the Union Course on Long Island.

At one point, Boston had won 36 of 37 contests. As the horse’s fame spread throughout America — and to England as well — Rives sold his interest in Boston to James Long, who offered to bet $50,000 and run Boston in four-mile heats against any number of horses the English cared to name. There were no takers.

With no suitable competition, Boston was placed at stud in Virginia in the spring of 1841 and covered 42 mares at a fee of $100 each. Late in the summer, he was put back in training and ran five four-mile heat races between Sept. 30 and Oct. 28. Boston won the first four of those events, but his form paled in comparison to before he took time off for stallion duty.

On Oct. 28, 1841, Boston suffered the most crushing defeat of his career at Camden. The first four-mile heat was won by a 4-year-old named John Blount. Fashion was three lengths back, but Boston finished 240 yards in the rear and was declared “outdistanced” and therefore ineligible to run in the remaining heats. Fashion emerged victorious over John Blount in the next two heats to secure the victory.

Col. Johnson and Long moved quickly to get a rematch. Terms called for a match race between Boston and Fashion at the Union Course the following spring with a $20,000 side bet. There was tremendous national interest in the event, which drew more than 70,000 people to Long Island on May 10, 1842.

Nine-year-old Boston carried 126 pounds against the 5-year-old Fashion, who got in with a feathery 111 pounds. Boston, under Hall of Fame jockey Gilbert W. Patrick, hit the rail late in the first heat and opened a sizeable gash on his left side. He competed gamely, but lost by a length. In the process, Fashion set a world record of 7:32½ for the four-mile distance. Fashion secured the victory in the second heat by some 60 yards without being extended by Boston to win in 7:45.

Boston returned to the races only three days later, facing Mariner, a half-brother to Fashion. Boston sulked through the first heat and lost, but blazed back to take the next two contests and win the match. Old White Nose ran three more times in 1842, winning twice. He ran once as a 10-year-old in 1843, winning a three-mile heat competition at Petersburg, Virginia, to run his total earnings to $51,700.

Boston’s success at stud was attained in the face of poor opportunities. In 1841 and 1842, he served two full seasons between racing campaigns. In 1843, Boston stood in Hanover County, Virginia, and in 1844 he was moved to Washington, D.C., where he stood in 1845 and 1846.

It was not until his final three seasons, when he was blind and feeble, that Old White Nose was afforded quality mares. He was shipped over the mountains during rough winter weather to stand at Col. E. M. Blackburn’s farm in Woodford County, Kentucky, in 1847. Quartered in a stable built of logs and through which wind howled at night, Boston caught a cold that further compromised his health.

By the spring of 1849, Boston could not regain his feet unaided after once lying down. A hammock was improvised in the stable and four ropes were thrown from the rafters to hoist Boston to his feet. Stable boys would then briskly massage his legs until Old White Nose could stand by himself each morning.

It was in this condition in the twilight of his life that Boston sired the great horses Lexington and Lecomte in his final crop. Lexington went on to become the most influential sire in American racing history. In January 1850, Boston was found dead in his stall. He led the sire list, posthumously, in 1851, 1852, and 1853.

Boston, considered by many to be America’s first great racehorse, was inducted into the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame as part of the inaugural class in 1955.

Media